“Premonition” by Olawunmi Shobola is a poem about love seen not just in the present, but through the lens of its inevitable end. It is not a lament, nor is it indulgently sentimental. Instead, it is a measured reflection on the quiet, almost instinctual awareness of heartbreak before it arrives. The poem unfolds in that precarious space where love is still whole but already fraying, where a moment of closeness is shadowed by the certainty of departure.

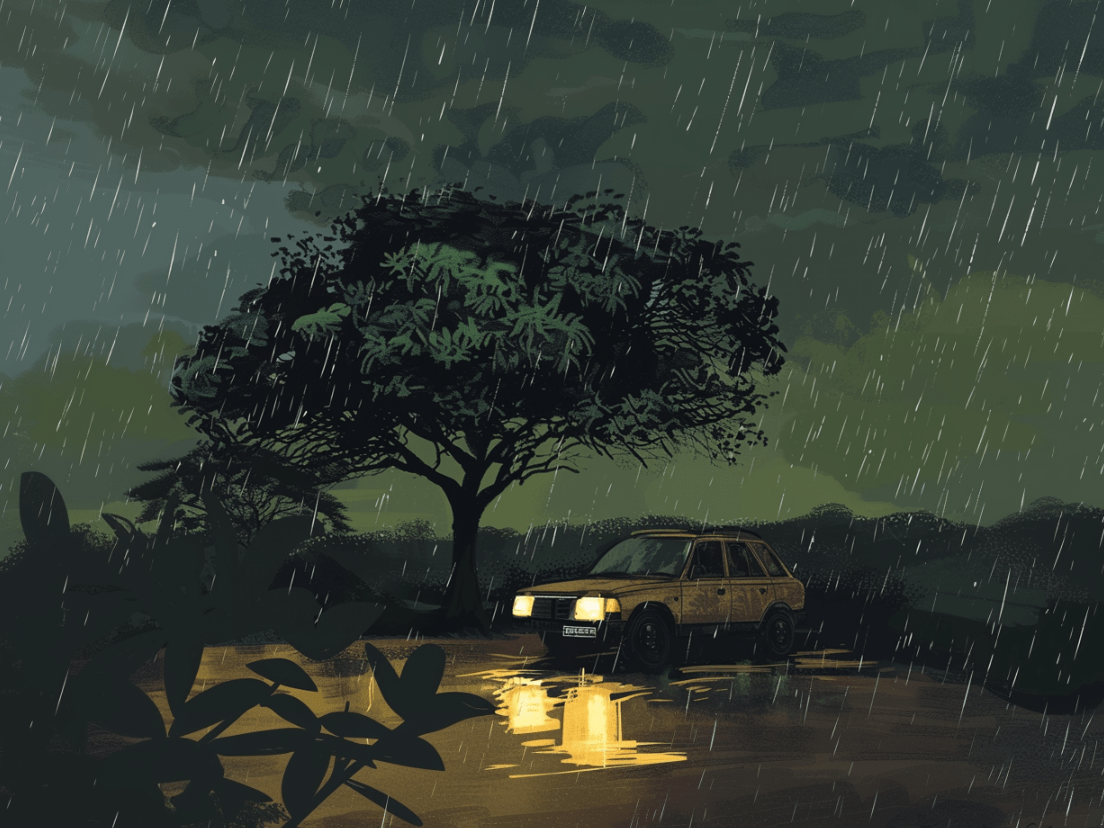

From the opening lines, the speaker transports us to a scene that is both intimate and cinematic. “There was this boy I liked / we’d sit in his car parked under the night sky, / chairs reclined, listening to Fela.” The details are spare yet evocative. The night sky, vast and endless, contrasts with the enclosed space of the car, creating a world that feels both boundless and claustrophobic. The reclined chairs suggest ease, a desire to linger, while listening to Fela adds layers of nostalgia and cultural specificity. Music is not just background noise here; it is part of the fabric of the relationship, a sensory detail that cements memory. Yet, there is something ghostly about the way it is recalled. The past tense of “There was this boy I liked” signals a quiet ache before we even reach the poem’s conclusion. This is not a love that endured. This is a love remembered, already gone.

What makes Premonition particularly affecting is its interplay between tenderness and discomfort, attraction and revulsion, devotion and inevitability. The boy’s habit of chewing raw onions is described as “the most disgusting thing in the world.” The imagery is strikingly unromantic. There is no poeticising of his habits, no attempt to filter them through the lens of affection. Instead, the detail stands in stark, pungent contrast to the quiet beauty of the night and the music. Yet, despite this, “my butt stayed glued to his seat.” This is where the poem subtly captures the absurdity of love. We endure the unpleasant, the ridiculous, the off-putting, simply because we want to be near someone. It is a strikingly human moment. Love is rarely logical, and the speaker does not attempt to rationalise it. She stays, despite herself.

The poem’s emotional crescendo arrives in the final stanza. The speaker watches the rain “rattle the roof of his car, / a matching rhythm to my beating heart.” The rain is more than just weather here; it is a motif rich with symbolism. It creates an enclosure, a sense of intimacy, but it also foreshadows the inevitable washing away of what is fleeting. Rain is an element often tied to transformation and endings. It can be cleansing, but here it is ominous. The word rattle is particularly important. It suggests not just sound, but disturbance, something unsettling beneath the surface. The heartbeat that mirrors this rattling reinforces the poem’s central tension. Love is present, but fear is rising alongside it.

Then comes the poem’s most devastating turn. “I’d grin as widely as I could / to mask the terror in my gut.” This is where the full emotional weight of the poem lands. The speaker is not merely enjoying this moment; she is performing for it. The wide grin is a shield, a desperate attempt to conceal what she already knows to be true. The use of terror rather than a milder word like fear or worry is a masterful choice. It suggests something primal, something deeply embedded. This is not just nervousness about a relationship’s future. This is certainty. The speaker knows, with the same quiet inevitability as the rain, that heartbreak is coming.

The final lines close the poem with quiet devastation. “That (I knew) he would become / my first heartbreak.” The heartbreak has not yet arrived, but it is already real. The use of parentheses around “(I knew)” is crucial. It gives the impression of a thought the speaker cannot fully voice, an aside that almost breaks the fourth wall of her own narrative. It also suggests an attempt to compartmentalise the truth, to acknowledge it without fully confronting it. This is not just hindsight; it is the slow, creeping knowledge that we sometimes try to suppress but cannot escape.

One of Premonition’s greatest strengths is its restraint. The poem does not dramatise its emotions. It does not beg for sympathy or over-explain. It does not lean into conventional heartbreak tropes of tears and regret. Instead, it captures the precise moment before loss, when love is still present, but its expiration date is undeniable.

The economy of language is another defining feature of this poem. In just a handful of lines, it evokes a relationship’s tenderness, strangeness, and inevitable end. There is no excess, no indulgence in florid metaphor. Every detail, from the boy’s raw onions to the rain’s rattling, serves a purpose. The poem understands that heartbreak is rarely a single catastrophic moment. It is a slow, creeping thing that sometimes announces itself long before it arrives.

The poem captures what some psychologists call anticipatory grief, the experience of mourning something before it is gone. This is common in relationships where one person instinctively senses the other’s departure long before it happens. The body often knows before the mind accepts, and Premonition gives voice to this quiet, internal dread.

Finally, Premonition succeeds because it is deeply, universally human. It is a poem about more than just a specific relationship. It is about the way we sometimes see heartbreak coming and choose to love anyway. It is about the absurdity of human attachment, the way we tolerate what repels us, the way we perform joy in the face of looming loss.

The poem does not need to tell us that love ends. It does not have to show us the aftermath. Instead, it captures something rarer and more complex. It shows the knowledge that something will end, even as we sit inside it, trying to hold on for just a little longer.