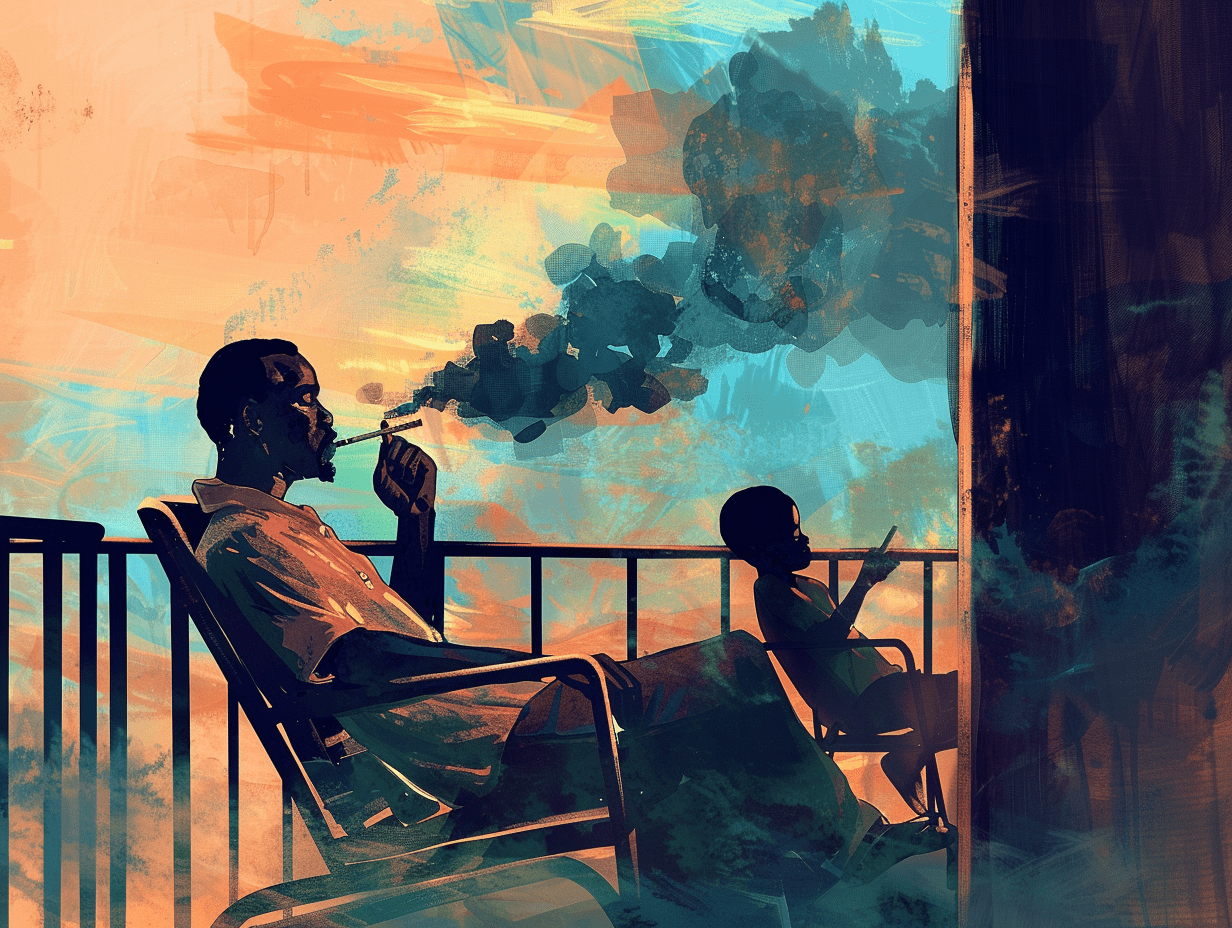

“Blood Ties” by Abu Ibrahim is a poem that moves with quiet devastation, lingering in the spaces between smoke, memory, and mortality. It does not simply depict addiction; it absorbs its weight, allowing the reader to inhabit its presence. The poem unfolds like a slow burn, its restrained voice amplifying the inevitable collapse at its core. Beneath its quietness, something unspoken implodes.

From its opening line, “I grew up in a hazy house”, the reader is submerged in a world where addiction is not a singular act but an atmosphere. The choice of the word hazy is deliberate, connoting not just literal cigarette smoke but also an emotional and psychological ambiguity, the fog of a life dictated by compulsion and helpless observation. The poet does not offer exposition. Instead, they unfold the narrative with delicate precision. Each line peels back a layer of lived experience.

A particularly striking quality of Blood Ties is its economy of language. There is no excess, no indulgence in elaborate metaphor for metaphor’s sake. Every word serves its function with surgical exactness, making the poem feel both deeply personal and universally resonant. The line, “For years, I watched a dimmed light / light up another dimmed light”, is an exceptional example of this controlled brilliance. At face value, it captures the monotonous, habitual nature of addiction. Beneath it, there is something more profound: a cyclical erosion, a passing of light from one dying source to another, an inheritance of destruction.

Inheritance is a crucial undercurrent in this poem. The speaker not only watches but learns, absorbs, and ultimately mirrors. The knowledge of addiction and mortality is imparted in grim increments. “I know how the future crumbles into ash” is a line that is both observational and prophetic. The theme of foreknowledge, the helplessness in the face of inevitable consequence, is deeply embedded within the poem’s structure. It is not just about a father’s demise but about the speaker’s own proximity to the same fate. This is cemented in the harrowing moment towards the end. “Halfway home, I asked to use the restroom at the mall and returned smelling like my dad.” The implication here is not simply nostalgia or association. It is the chilling realisation of repetition, of history looping back upon itself.

The poem also touches on the paradox of resilience. Despite the expectations set by science and statistics, the father lingers. “And against the odds he is still here / still here but shockingly leaving soon.” The juxtaposition of still here and shockingly leaving soon reveals the paradox of slow death. It is the peculiar experience of watching someone erode over time but still feeling unprepared when the end finally arrives. There is no catharsis in this knowledge, only a suspended grief, stretched across years of knowing.

Perhaps one of the most masterful strokes in Blood Ties is its refusal to be overtly sentimental. Even in its most heart-wrenching moments, the poem does not reach for pity. Instead, it offers a stark, unembellished truth. “Nothing prepares you for death, / not even when you see it coming.” This line encapsulates the poem’s philosophy. Knowing does not soften the blow. Awareness does not lessen the weight of loss.

The closing lines, “We locked eyes, said nothing. Because death leaves us all speechless”, bring the poem to a fitting and inevitable conclusion. Here, language itself falters and becomes insufficient. The silence at the end is not merely about grief but about the futility of words in the face of the inescapable. The speaker, once an observer, has now become a bearer of the same unspeakable truth.

Blood Ties is a poem of witness and inevitability. It does not offer solace, nor does it attempt to moralise. Instead, it stands as a stark, elegant documentation of how addiction and mortality intertwine, how knowledge does not equate to power, and how, despite all our awareness, we remain unprepared for the moment the dimmed light finally goes out.